A particle accelerator is one means to explore the nature of reality. A canoe is another. Since I’m not a physicist, I rely on my canoe. But what could a canoe possibly reveal about reality? As a recent empty nester, I carved a dugout canoe from a big tree and led a small expedition down the 2,341-mile Missouri River from Three Forks, Montana to St. Louis, Missouri. Throughout the five-month journey we experienced statistically improbable good luck, so much so, that we avoided talking about it for fear of jinxing that luck.

Blessed with minor miracles on a near daily basis, we acknowledged the improbability of our good fortune, yet hesitated to claim it as something we either owned or controlled. At the same time, serendipitous encounters featured so prominently in the expedition that we learned to anticipate improbable good luck as the journey proceeded.

Based on past experiences, I’ve learned to have faith in the Universe to trust that everything will work out as it should be, even if not always as anticipated. The challenge is to maintain that deep faith, much like a trust fall, where you fold your arms across your chest and fall backwards, trusting friends to catch you. I am not a reckless person. I wear my life jacket in a canoe as faithfully as I wear my seatbelt in a car. Nevertheless, trusting oneself to the river for five months in a canoe requires a degree of faith regardless of preparation or experience.

Looking back a year after successfully completing the expedition, I feel more comfortable broaching the mystical aspects of the journey, especially the serendipitous encounters of the canoe kind.

Prelude to Passage

The magic started long before the trip officially began. I had been considering one of three possible epic adventures: hiking the Appalachian Trail, bicycling across the U.S., or paddling the Missouri River from its origin at Three Forks, Montana downstream to its confluence with the Mississippi at St. Louis. Carving a dugout canoe was an unrelated dream that converged into place at the right time.

My friend and fellow Lewis and Clark history buff Steve Morehouse donated his twenty-year-old weathered dugout canoe as a museum piece for my primitive skills camp. His ponderosa pine canoe was twenty-seven feet long from stem to stern, and he’d had a stout custom trailer built to haul it. Having retired the canoe, Steve sold me the trailer at a reasonable price, and I became the owner of a dugout canoe trailer. I don’t know how many dugout canoe trailers there are in the world—possibly only one—and it landed in my lap just prior to carving my own dugout canoe. Serendipity graced the way for the entire process of carving the canoe, preparing for the trip, paddling the river, and subsequently writing a book about the experience.

I was especially fortunate to connect with Churchill Clark, the great-great-great-great grandson of Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Churchill has made a career out of “carving canoes and paddling trees,” and he’d just finished an eighteen-month project to carve two dugout canoes from a tall cottonwood in Missouri. His schedule coincidently aligned with mine to come to Montana to carve a dugout canoe at my wilderness survival school.

I run two separate programs, Outdoor Wilderness Living School LLC (OWLS) for youths and Green University LLC for adults. As I learned when buying land the wilderness camp, serendipitous luck isn’t always direct or obvious.

I had felt an intimate connection to this property the first time I saw it for sale, but the asking price of $340,000 for twenty-one acres was way beyond my means. Then came the Great Recession of 2008, and the price started to fall. I felt certain it was the right property and my offer was accepted to purchase the property for $200,000. However, the contract fell through because the bank refused to finance the loan while I was in the midst of my divorce. Meanwhile, the price fell further, and I eventually bought the property for $165,000, just under half the original asking price. I intuitively felt a connection to the property from the get-go, but it took four years to prove up. We later named the parcel River Camp.

In the case of the canoe, a large cottonwood fell at a public campsite that I help manage as president of the Jefferson River Chapter of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Churchill arrived in spring ready to start carving, but declared that the log wasn’t quite big enough. After bringing him to Montana and organizing both our schedules around the canoe project, we went into panic mode to find a reasonable substitute.

Big trees are exceedingly rare on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains, and the only thing we could find was a 10,000-lb. Douglas fir at a nearby sawmill. I had recently volunteered to help my new next-door neighbor unload a big pile of beams off his flatbed trailer, so I asked him about moving the log. Coincidentally, he drove past the sawmill every day on his 90-mile commute to work so he could deliver it without hassle. Minor miracles happen all the time.

As for the Douglas fir log, it was hard, full of knots, and prone to cracking and splitting, everything that a canoe wood shouldn’t be. Was this a miracle or a curse? We used adzes and chopped by hand, then compensated with power tools to saw, shave, grind, and sand the knotty wood. It took more than three months to complete the canoe, but true to Churchill’s talent, the canoe was a work of art, and a nicer watercraft than we could have carved from any cottonwood tree.

Belladonna, as I named the canoe, is a beast of a boat. Churchill’s previous canoes were substantially smaller, weighing less than 300 lbs. This one was twenty feet long and weighed in at 500 to 900 lbs. I removed an expansion joint from the dugout canoe trailer, matching the canoe and trailer perfectly to each other.

As the beautiful canoe took shape, it became evident that I would be paddling the Missouri River rather than hiking the Appalachian Trail or bicycling across the U.S., and I would do it like Lewis and Clark, in a real dugout canoe instead of a modern plastic one.

We did our maiden voyage with Belladonna on Montana’s Marias River. I planned a two-week canoe trip with one week on the upper river and reservoir, followed by a portage around the dam and another week on the river below the dam. Strangely, none of my friends or co-adventurers were available for that first week. As it was, we needed an extra week to prepare the canoe. Good thing too, because it rained a whopping 12 inches in the upper Marias watershed that week, an entire year’s worth of precipitation dropped over two days. That could have been a disastrous expedition! I was grateful that we failed to launch the expedition on time. The following week was sunny and dry, so we paddled the lower river below the dam where controlled water releases were precisely ideal for our canoe trip.

We faced one other potentially serious problem that trip. The boat ramp at the end of our run wasn’t a ramp at all, but a slippery clay bank with a muddy drop where the boat trailer would be utterly useless. The canoe was too heavy to lift or even drag easily without a winch. But miraculously there happened to be seven strong Hutterite men standing around, dressed in their Sunday best, as we paddled to shore. This is a fishing access site in a remote, sparsely populated region of rural Montana where we wouldn’t have expected to encounter anyone. How was it that they were there at that precise time? The Hutterite men were thrilled to pull on the front of the canoe from dry land while our crew got in the mud pit and pushed from behind, dragging the canoe out and up onto a bank high enough to back the trailer under the bow.

Some people might dismiss such serendipitous experiences as mere coincidences, yet there is a statistical improbability to consistently being blessed with good luck through the incidents above and throughout the subsequent five-month expedition down the Missouri River.

Manifesting Good Luck

Good luck is manifested in different forms. The Boy Scout motto, “Be prepared” is an excellent way to cultivate luck. As an experienced canoeist and wilderness survival instructor, I was well prepared to lead a 2,000-mile expedition. I’ve led numerous canoe trips and wilderness expeditions before, even if not nearly as long in distance or duration. But I also understood that freak accidents happen and no level of preparedness can ensure good luck in a bad situation. Ultimately though, every wilderness adventure becomes a journey of faith that everything will work out for the best.

Rather than paddle the Missouri alone, I invited friends, former students, and complete strangers to join the expedition to explore the river. In the vetting process, I relayed a story I’d heard from a student in one of my wilderness survival classes. He told of climbing a mountain in the Himalayas where the guide explicitly instructed him Not to step off the trail. Well, he did, and he went careening down the icy mountain on his butt, he had the good fortune of shooting right over a crevasse without falling in. He skidded to a stop without hitting any rocks or breaking any bones. It was a great story, but as I emphasized to my prospective crew, I would rather have boring companions than reckless thrill seekers. I wasn’t interested in heroic tales of survival rooted in poor choices.

Out of the five-man crew that began the journey, four of us made it to St. Louis, and we were indeed a boring lot, “the most boring crew ever,” as I praised them mid-journey, and that was key to our success in achieving the mission and doing it without significant incident or injury.

I studied the river in great detail over the winter before our expedition, tediously mapping out potential campsites and GPS coordinates for likely stops along the way. I was new to GPS devices, and in retrospect, the cell-enabled iPad I brought along was useless along most of the river corridor, where it was necessary to hike up to nearby mountain tops for a cell signal to determine location.

As luck would have it, Scott Robinson signed onto the endeavor and volunteered to obtain the necessary GPS equipment and learn how to use it proficiently for the expedition. Scott was a novice at wilderness skills, but quickly became chief navigator and effectively co-captain of the expedition. His GPS tracker accessed satellites everywhere along the journey and displayed our location, route, and distance to predetermined campsites on his connected smart phone.

In principal, GPS mapping isn’t required for an expedition that largely consists of following a river, and Lewis and Clark certainly didn’t have it. Yet, there were moments when it seemed indispensable, especially on big man-made reservoirs where it was extremely difficult to determine the difference between large bays versus the main channel of the river. GPS enabled us to find public lands for camping and hiking, and critically enabled coordination and planning with people from the outside world for meeting and portaging the beast of a canoe via trailer around the many dams.

Good planning helped ensure good luck. Yet, no matter how carefully one plans for all contingencies, it is impossible to control all variables. There are moments where survival ultimately depends on serendipitous good luck, the statistically improbable minor miracles that occur with surprising regularity throughout our lives.

The River as a Mirror

In western culture we are taught that rivers are functionally inert. Water is H2O, two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen. Accumulate billions of trillions of water molecules and we have oceans, lakes, and rain. Rain deposits water molecules upon high points of the landscape. Rivers result from gravity dragging water molecules downhill towards the oceans. H2O itself is theoretically lifeless and lacking in soul. Paddlers, however, have an intimate relationship with water, and those who are most experienced will assert that science is incomplete.

Paddlers find that rivers often reflect one’s life circumstances. A person struggling with anger and darkness in the aftermath of divorce may be confronted by brutal conditions on the river, a never-ending onslaught of pounding storms, waves, and unrelenting wind. Just as a boxer works out his fury on a punching bag, a paddler beats the water with his paddle. The river beats him back and nearly breaks him, but through perseverance, the paddler achieves his goal, thousands of miles long, overcoming not just the river, but more importantly, himself.

Having faced many challenges in my life, I know how to grit my teeth and bear discomfort to the end. This time I approached the river with nothing to prove, and more than anything, the desire for a well-earned extended vacation. The principal challenges we faced were more symbolic than substantive, and served as early tests that we overcame to earn our admission to the adventure of a lifetime.

Missouri River thru-paddlers typically launch in May, but because I teach outdoor survival skills to public school kids, we delayed until the first of June. May weather is generally turbulent in Montana, but May of 2019 was especially cold and wet with multiple rain and snowstorms, which miraculously landed on gap days between public school programs. Summer arrived gloriously in time for our big launch.

I originally envisioned leading an expedition of about a dozen paddlers, but trusted the Universe to provide the appropriate crew. Camping at the Fairweather Fishing Access Site that first night, I realized we had precisely the right-sized crew. With five of us in the core group, intermittently joined by other paddlers, we were big enough to enjoy diverse company, but small enough to operate with informality. In contrast, leading a dozen paddlers would have turned the adventure into a military operation to coordinate daily logistics, establish campsites, rotate cooking duties, delegate tasks, and maintain harmony and discipline. Listening to a louder group camped nearby that first night, I found it refreshing that our group was small enough to hear each other.

We encountered our first significant challenge just twenty miles downriver when the boat ramp was closed at the Toston Dam, necessitating a manual portage of a canoe that might weigh as much as 900 lbs. when empty. We overcame the challenge as a team, weighting down the stern to raise the bow enough to winch it up onto the grass. We moved the winch from tree to tree, using PVC rollers under the canoe to glide over a lawn to the parking lot. With the aid of a car jack, we raised the canoe high enough to back the trailer under it. We overcame this unexpected obstacle with relative ease, gaining the confidence that we could handle whatever we faced, while praying we wouldn’t have to do it again.

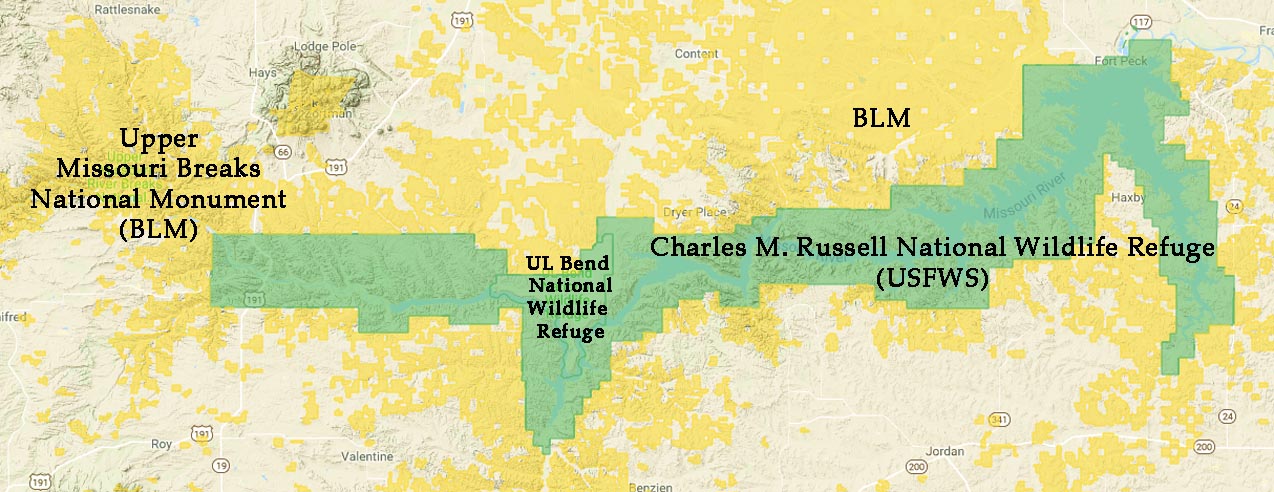

When researching the trip in advance, my principal concern was dealing with the big winds on the many reservoirs of the Missouri. Fifteen dams hold back 700 miles of flat water, the equivalent of paddling from Seattle to San Francisco on a lake, except that like the ocean, the lakes are seldom flat. Winds whip across the open waters kicking up waves that can quickly swamp a fleet of canoes.

Imagined fear came to life on our first big reservoir, paddling onto Canyon Ferry Lake just 70 miles into our journey. Paddling into a strong headwind, we moved parallel to the rocky shore where landing was impossible, yet forward momentum was negligible. For hours we paddled into the wind seemingly going nowhere, until we finally reached a sandy shore. My paddle partner and I went to shore, but the heavy dugout parked like a log and the waves hit her broadside, hopping over the gunnels to swamp her in seconds. Within moments we had all our sopping wet gear strewn across the beach, yet still we could not bail the canoe as fast as new waves continued to fill her up. But then the winds miraculously came to an abrupt stop. We were grateful for the opportunity to bail the canoe, re-organize our gear, and continue shortly thereafter.

While I intended to paddle every reservoir in Montana, I dreaded facing bigger lakes downstream in North and South Dakota. On Canyon Ferry we had an opportunity to test an idea I’d had for traversing the big lakes: hitch-hiking. Local paddler Jim Emmanuel had previously paddled the entire Missouri River, and he came to visit our expedition via motorboat, so I inquired about a trial run, towing us across the lake behind his boat. Towing all the canoes was impractical, so we hitched up Belladonna for the test ride.

Strangely, gale-force winds blew up out of nowhere as we left the other canoes behind. They retreated to shore while we sped down the lake. We moved at what seemed like fantastic speeds, plowing through big waves that threatened to swamp us at any moment. I steered carefully using the paddle as a rudder to maintain alignment behind the motorboat or risk being swamped if we slipped crosswise to the waves. It was a terrifying journey, yet we seemed to blow by several miles in a matter of minutes until my paddle partner up front was soaked and chilled and signaled that he wanted to stop. We cut loose and headed for shore, the gnarly winds subsiding as magically as they had started moments before. The rest of the crew never bothered to launch in the big winds, and much to my dismay, we had only traveled one-third of a terrifying mile in our motorboat adventure. The crew paddled their canoes across the now calm waters to join us while I started a fire to warm up the nearly hypothermic Chris, and we established camp there for the night. Clearly, my mastermind plan of hitchhiking was not the answer to traversing the lakes!

Timing is Everything

Our society largely defines reality as K-12 education followed by a college degree, a career and family, a mortgage and bills, followed by retirement and a slow death in an easy chair in front of a television. Superseding this basic narrative, some people view reality as a contest between good and evil, God and the Devil, to win your eternal soul. Other people see reality in strict Darwinian terms, that we are apes wearing clothes and life is a random accident without meaning or purpose.

I prefer a worldview from physicists, that our atoms consist primarily of empty space, that our building blocks are force fields of energy rather than actual substance. Our bodies and everything around us consist of energy, every rock, tree, mountain, and river, and within that energy exists unlimited possibilities, including the possibility that life is far more interesting than advertised and events are less random than they seem.

For example, it is easy to watch the clock and stress out about prescheduled appointments. But what happens if we trust that we are exactly where we need to be at any given moment? How many times have I been late to a meeting only to discover that it was delayed, canceled, or didn’t require my participation?

I attended the Winter Count primitive skills gathering in Arizona four months prior to the launch of our expedition, bringing potential crew members with me. Two others drove down separately from Colorado to meet and talk about the expedition. I’ve never owned a mobile phone, which admittedly complicates meet ups. Nowadays, people text back and forth and adjust their destination and estimated time of arrival on the fly.

Without a phone, I rely on an older form of coordination, one where you get up and start walking when the time feels right. In this case an instructor relayed a message to meet one of the arrivals by the corrals at a specified time. Being skeptical, I brought a book and read for two hours while nobody showed up. Winter Count is held in the desert with 500+ people spread out in camps over 200 acres among big rocks, cacti, and shrubbery. Finally, I felt the urge to get up and walk. Moments later, I randomly bumped into one of the guys, and within minutes, without a designated time or place, all six members of the meeting had accidentally arrived at the same place.

I’ve often wondered how mated pairs of birds keep track of each other. Companion calling helps two birds track each other through the woods, but if they were to drift out of earshot there would be no obvious reference point to reconnect, especially when migrating over thousands of miles. I imagine they too have the ability to ‘randomly’ fly to undesignated meeting points.

For the big canoe trip I bought the cell-enabled iPad to handle emails along the journey, but still didn’t have an actual mobile phone. During our stay in Fort Benton, I’d hoped to connect with German explorer Dirk Rohrbach and his partner Claudia Axmann. Dirk paddled the Missouri source-to-sea the previous year, nearly 4,000 miles from the smallest rivulet in the mountains downstream to the Gulf of Mexico. He returned to retrace the river for additional photography. We had no scheduled meeting place or time, but I ducked into a coffee shop for hot chocolate, a brownie, and email. I was still in line at the counter when Dirk and Claudia walked in the door, having just arrived in town.

Serendipitous timing is neither a superpower nor particularly uncommon. Many people have a talent for walking in the door precisely at meal times, even without a consistent dinner schedule. Merely needing to talk to someone may bring that person to the door or the phone.

In comparison, coordinating meetings via phone or text often requires constant renegotiation of the time and place. Yet the body knows what the mind does not. I’ve developed a preference for randomly or instinctually arriving in the right place at the right time without a pre-coordinated plan. I worry that people will lose that ability when relying too much on technology.

On the other hand, we found texting essential to coordinate with people from the outside world to assist with portages around the many dams of the Missouri River.

Some Missouri River paddlers have packed wheels to portage their own canoes in the determination to traverse every mile of the river. Others have paddled without a portage plan, hitching rides from helpful bystanders at each dam. In our case, paddling an absurdly heavy dugout canoe required bringing the custom trailer to portage each dam. We didn’t have a backup crew to follow us to St. Louis by road, so we brought the trailer without a truck, relying on friends, family, and complete strangers to hand off the trailer from dam to dam all the way to St. Louis.

Coordinating a portage plan might easily have turned into a logistical nightmare. There are fifteen dams on the Missouri, five of which are portaged as one around Great Falls, Montana, while other dams are in remote, sparsely populated areas. Yet, creating a portage plan required shockingly little effort, slightly more than no work at all, thanks to the generous outreach of those who volunteered to help us and the serendipitous good timing of everyone’s schedules.

To coordinate with drivers, I’d worked up a theoretical timetable for the expedition across Montana, then asked family and friends to help out with the local portages. I anticipated a string of back and forth emails and phone calls, but everyone’s schedules magically lined up with each other, so that there was always someone to assist with portaging, even hundreds of miles from home.

Later we were assisted by “river angels,” volunteers who kindly moved the trailer from one dam to the next. Some we connected with online in advance, while others were complete strangers we met on shore who volunteered to drive the trailer to the next portage point. And after all the dams were behind us, we were still 800 miles from St. Louis, but a local river angel happened to be driving that way for a meeting and delivered the trailer to our final destination.

In planning for the adventure, I had hoped to visit the American Prairie Reserve’s bison restoration project north of Fort Peck Reservoir in north central Montana, but hadn’t made contact ahead of time. As luck would have it, I met a bird photographer at Fred Robinson Bridge, the last outpost of civilization before the big reservoir. He had just come from the Enrico Education Center at APR and provided me with a name and email to reach the on-the-ground contact there. Arriving at Fourchette Bay a week later, we hiked up through the badlands and ponderosa pine forest to reach cell service. By chance we reached Hila Shamoon via email and she drove out to pick us up. We were doubly lucky to accidentally walk to the ideal pick-up point, since the other roads were impassible with wet clay due to recent storms. Timing is everything, but it does require a degree of faith and trust in the Universe.

Manifestations

The idea that success entails hard work is deeply embedded in western culture, and I’ve worked harder than most to make my dreams come true. Having clawed my way forward an inch at a time for decades, I found it unsettling that other people could simply broadcast their dreams to the Universe and be effortlessly showered with all that they asked for and more. I went at life like a bulldozer, trying to physically shape the world to my ideals. All that blew up in my face with the loss of my marriage, the fracturing of my family, and having to start my life anew. The experience ultimately taught me to cast my Dreams to the Universe without being in such a hurry to achieve them, accepting that events would unfold if or when the time was right.

Proceeding downriver, I still hadn’t come up with a plan to overcome 400 miles of flat water paddling on reservoirs through the Dakotas. I had nothing to prove and saw no benefit to paddling a heavy dugout canoe against choppy wind and waves for weeks on end. I was here to explore the river, not beat myself up and incur repetitive stress injuries trying to overcome artificial conditions on man-made reservoirs.

I had considered portaging around all the lakes, but didn’t want to miss anything. My test run hitch-hiking behind a boat with a tow rope on Canyon Ferry Reservoir was a near disaster. My only other idea was to attach a motor to the canoe and power across the reservoirs when the wind wasn’t blowing. But I had run out of time to research the idea, so we paddled downstream with no motor and no plan. I was, however, contacted by a guy who liked my books and wanted to drive up from Georgia to join the expedition for a week. He could only get away in early August, connecting with us in western North Dakota. When he first asked what he could bring, I couldn’t think of anything, but when he inquired again, I asked if he happened to have an outboard motor lying around.

Charles Tatch gifted us with an outboard motor, clamps to attach the motor to the dugout canoe, gas cans, Georgia peaches and much, much more. We padded together for a couple days on the river and the upper portion of Lake Sakakawea before taking a three-day layover at Tobacco Gardens Resort where we installed and tested the outboard motor. We lashed one of the other canoes to the side of the dugout canoe like an outrigger and towed the third canoe behind us. With the aid of the motor, we could roar down the reservoir at 4.5 to 5 mph, more than twice as fast as we could paddle. It still took us six weeks to cross all the lakes of the Dakotas, much of that time spent on shore waiting for winds to abate so we could get back on the water. But when fair weather came, we could cover as much as forty miles in a single day, greatly facilitating our downstream progress before we parted with the motor.

Charles stayed with us for a total of ten days. He asked how one manifests something into existence, and I said I didn’t know, but here he was, like an Angel from Heaven, arriving at exactly the right time with precisely the right equipment we needed to successfully traverse the lakes. How many other people would do that?

North Dakota includes a sixty-mile section of free-flowing river between reservoirs, so we untied the “Contraption,” as we called our motorized watercraft, and returned to paddling. We normally avoided paddling in the rain, but the day we did was the day we also hoped to tour Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site near Stanton, North Dakota. The site was a few miles off the river, so we chose the closest point and tied the canoes at a private boat ramp and started walking in the rain. A hundred yards down the road, immediately after walking past the Private Property signs, we encountered the landowner driving home.

Bill Marlene rolled down his window, and after we explained what we were doing, he kindly offered us a ride to the historic site. Then he told us about this guy he knew named Churchill Clark who carves dugout canoes. Such was the serendipitous nature of our journey that we would stumble into a friend of a friend a thousand river miles from home. Bill not only gave us a ride to and from the historic site, he provided a warm cabin for us to bunk in through a cold, rainy night.

Not far downriver, we were approached by three guys in a motorboat who yelled out, “Are you guys the Corps of Rediscovery?” “Yeah, you found us,” I replied, assuming they were tracking our progress online, But they had not heard of the expedition; it was just a lucky guess made in good humor. Shortly thereafter, we pitched our tents on the lawn at Clete Burbach’s home north of Bismarck, joining his family and guests for a big steak dinner with fresh corn, mashed potatoes, and a big green salad.

Clete’s next door neighbor was a retired veterinarian who happened to have some spare medicine available to give our expedition puppy a free distemper/parvo shot. Jubilee was a stray found on the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana. Chris and Josiah had walked into Wolf Point for ice, and didn’t return for an unusually long time, ultimately wandering back to the canoes with this two-month old puppy. They explained the rationale by which they determined it was a legitimate stray and brought her on board. Chris tried to schedule an appointment for the shot in Bismarck, but none of the veterinarians could fit it in their schedules. Chalk another one up to serendipity, that the neighbor came to the rescue. The need was broadcast to the Universe, and the answer manifested itself in the generosity of strangers.

Not far downriver, we stopped at a campground where the host went the extra mile to make sure we were well situated with everything we needed. Then he brought us a big lasagna baked by his wife for a dinner party that was unexpectedly canceled. Was this a random event or serendipitous timing, or did we somehow unknowingly manifest this situation into existence? I don’t know, but the lasagna was delicious as was the gracious hospitality of our camp hosts.

Given all the minor miracles that occurred on our trip, I cannot claim to be in control of anything. If I could manifest my dreams into reality, I would have met my ideal life partner, and I would have won the lottery to invest in conservation projects and green business enterprises to make the world a better place. I’m still waiting.

UnManifest Destiny

From nothing, the Universe exploded itself into existence, yet instead of celebrating the miracle of life, people want to get wasted on the weekends to forget the misery of the daily grind. People are more interested in watching sports, smoking a joint, or going shopping, rather than marvel over the mystery of life. But to me, every day is a new opportunity to re-ask the question: What is the nature of reality?

Although born in California, I am otherwise a fourth generation Montanan on both sides of my family lineage. Through my childhood years, we drove to Montana every summer to visit family, and I was thrilled to permanently return to Montana at the age of twelve to begin junior high. However, I’ve always struggled with the fact that my Montana Dream came true only because my father died of cancer, thus freeing the family from his electronics career in what later became known as the Silicon Valley.

The loss of my father at an early age enlightened me to the shortness of life and the necessity of living one’s dreams without delay. That early awareness of mortality is not a gift I would wish on anyone, yet it propelled me forward in pursuit of my dreams. Without that lesson, it is possible that I would have chosen a more conventional career-oriented path without building my own home or seeking great adventures, like paddling the Missouri River in a dugout canoe. Through chance events or Divine plan, my fate has always been linked to that of my father with uncertain questions about what that means. I’m fairly certain I did not manifest his death to live my dreams.

On the river we grappled with a similar issue in regards to floodwaters. We paddled the Missouri through one of the wettest years on record, with heavy precipitation and runoff continuing all season long. We observed, with a twinge of guilt, that billions of dollars in downstream damage gifted us with optimal river conditions for our expedition.

I had anticipated a parched, dead prairie landscape where we would be plagued by searing heat and unrelenting sunburns. Yet with rainstorms sweeping through twice a week, the reservoirs were full to the brim and the land was as green as spring all summer long, so green that we enjoyed harvesting mushrooms on the prairie.

Had we paddled the river in a dry year, we would have struggled to navigate around sandbars in the river. Of primary concern was the point where water enters a reservoir and slows, dropping its sediment load to create miles-long mazes of muddy mire, sandbars, and dead-end channels that can thwart forward progress. Reservoirs are also ugly as they drain down, leaving a bathtub ring of mud, sometimes hundreds of feet wide, that must be transversed to reach solid ground and vegetated surfaces. The Missouri River remained optimally beautiful from one end to the other.

Abundant rain would seem a bad deal for a canoe expedition, but almost without fail, we reached our chosen campsites moments ahead of incoming storms, putting in the last tent stakes with the first drops of rain. On wetter days we stayed put and enjoyed reading or journaling, so we seldom paddled in the rain.

Launching June 1st put us behind the floodwaters for half the journey. We caught up with the flooding below the last dam, with more than 800 miles left to reach St. Louis. In some places the river was miles wide, flooding out through the trees with no land in sight, which was disconcerting, but not particularly dangerous. The river is so flat that floodwaters resemble a slow-moving lake. Boat ramps and marinas were flooded out, making it nearly impossible to get boats on or off the river. We largely had the river to ourselves with little other boat or barge traffic. State parks mostly waived camping fees, and it felt like we landed on Free Parking wherever we went.

Members of the crew frequently noted our fortuitous luck while trying to be sensitive to those who suffered flood damage, including some of the river angels who were so gracious with their hospitality under difficult flood conditions.

The biggest rainstorm we encountered hit at Decatur, Nebraska, which fortuitously had a large sheltered picnic area. The park manager advised us to pitch our tents on the concrete slab under the shelter, where we waited out two long days of rain. The rain raised the already flooded river by another foot.

Some events seem fated to happen, even if not always obvious why. Trapped under the same roof was Dan Hurd, who was sixteen months into a journey to bicycle the lower forty-eight states for suicide awareness, peddling north and south with the seasons as he gradually moved West. Dan became an honorary member of the expedition, joining us for the next week as we traveled together, us by water, and him cycling by land. Dan typically arrived in camp ahead of us, securing permission and connections before we caught up.

A week after parting ways, we bumped into Dan again very briefly in St. Joseph, Missouri while touring the home of outlaw Jesse James, where he was killed in 1882. The following day Dan cycled into the historic tourist town of Weston, Missouri where resident Wendy Maupin recognized him from our online posts. It’s a small world. I didn’t know Wendy personally, but she stopped by my house in Montana earlier in our trip to see her friend Churchill Clark, who was there for a few weeks to wrap up old business. Now we were in her neck of the woods, and she brought Dan and a kayak out to join us on the river. We spent a couple more days paddling together before parting ways again. Eleven months later, Dan’s ongoing bicycle adventure brought him to my home in Montana. Dan later interviewed me for his Movement Monday podcast. For unknown reasons, destiny connected us in a rainstorm and our paths remained intertwined.

Of all the mysteries of our Missouri River Expedition, one of the most puzzling to me was the sudden lack of emails. At home I organize my life around the constant effort to pick away at projects in my inbox. Some emails are easily answered. Others require hours of work to complete a task prior to responding. Being self-employed, I’ve enjoyed a great deal of freedom to go on lengthy vacations and travel the world, yet self-employed people, and particularly self-employed writers, are seldom ever truly free. My vacations include regular stops for WiFi in coffee shops. Still, after three or four weeks abroad, I typically have a long list of unresolved emails to which I’ve promised a more thorough response upon returning home.

In preparation for the Missouri River expedition, I bought the iPad with cell service so I could manage emails whenever cell service was available. Most people who email me would not know that I was out of the office for five months, yet inexplicably, the emails largely dried up when we hit the water. My sister kept my publishing business running and checked my voice mail weekly, but shockingly very few emails appeared in my inbox.

The lack of email correspondence was especially surprising because a day before the expedition I sent a mass email out to 500 newspapers in the states along Missouri River route with the first installment of what I offered as a free weekly column from the river. I wasn’t sure if all 500 newspapers might reply to my query! I’d always dreamed of writing a newspaper column, and several newspapers along the route did carry the weekly installments. With the initial email ready to go, I hovered over the Send button, not sure if it was a good idea or not, then finally said, “What the heck…” I clicked the button committing me to writing the newspaper column and a potential blowback of hundreds of email queries in response, yet very few found it necessary to bother me with questions.

Afterward, I had no intention of turning the newspaper column into a book. I intended to be done with the river trip when we reached St. Louis, without spending the next two years of my life turning it into a story. But writing the newspaper columns was an excellent writing exercise that pushed my abilities as an author, and it was evident within a few weeks that I was writing a book while on the water.

The book was also evident to Joanna Walitalo, an artist who did hundreds of line art drawings of plants on wooden blocks based on illustrations in my book Botany in a Day. Joanna followed my blog and offered to illustrate the Missouri book while we were still paddling the river. Her illustrations precisely complemented the photo-rich book, which she presented on yellowed paper with mildew spots that provided the perfect backdrop for the historical-themed book.

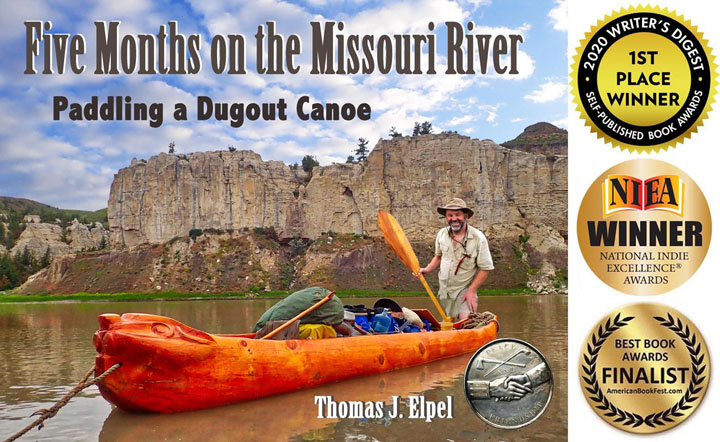

The book, Five Months on the Missouri River: Paddling a Dugout Canoe, was 80 percent written when we reached St. Louis. With the timely delivery of Joanna’s excellent illustrations, I finished formatting the book in just four months and held it in hand shortly thereafter. I was soon honored with three awards for Five Months on the Missouri River, including the Writer’s Digest First Place Award for Nonfiction. Not bad for a book I didn’t intend to write.

Happy Accidents

As the old Hank Williams Sr. song goes, “I’ll never get out of this world alive.” The world is a dangerous place, and there is more than enough suffering and misery to go around. I’ve been fortunate to enjoy largely good health, aside from several days in an oxygen tent as a baby, bouts of asthma as a child, and a bee allergy that persisted until adulthood. Our culture teaches us that health issues arise from the physical world, such as a bad diet, toxins in the environment, and unfortunate accidents for which we are unwilling participants. While that seems logical enough, I’ve often wondered if all accidents are truly accidents, perhaps some are physical manifestations of emotional pain.

As an avid hiker, accustomed to long rambles in the mountains, I have been keenly aware of the importance of knees. I saw my Great Aunt Evie sidelined to a sedentary life by bad knees. For me, the loss of mobility equated to the loss of identity, the greatest physical loss I could imagine. In retrospect, it seems hardly surprising that I suffered a torn ACL in my left knee at the same time my marriage and family came unraveled, and with it, my identity as a family man. The physical pain of the injury and the loss of mobility matched the emotional pain of my broken heart and the wholesale loss of my identity.

ACL reconstruction surgery gave me a new knee, but a knee with pain that directly reflected the continuing pain of my broken heart. On good days I could walk three miles out and three miles back, by which time I needed a couple days to recover. On the worst days, mired in the heart aches of the past, my knee felt like a jumble of separate parts grinding together as if it could all come flying apart at any moment. But as my heart healed, so too did my knee.

Paddling the Missouri River was, in part, an opportunity to finish rehab on my knee by returning to the earth, to live on the ground as our ancestors did. I enjoyed five months of getting in and out of the canoe, sitting around the campfire, crawling in and out of the tent, and hiking the surrounding countryside. With my kids out of the nest, the canoe trip was therapy for my knee and soul together, marking the start of a new chapter in my life. I was rarely stationary at any of our camps, coming and going, wandering in circles as long as daylight allowed. My longest hike of the trip was about fifteen miles, entirely pain free, giving me the assurance that I could resume multi-day walkabouts through the wilderness.

We can never truly know what curve ball life will toss our way, but as a result of the knee injury and other lessons learned, I’ve strived to pay deeper attention to the intuitive internal compass, constantly questioning the path ahead. Too often we force ourselves down paths that don’t feel right in the name of duty, obligation, and the almighty dollar until our only means of respite is physical injury. Overworked and overstressed individuals are at risk of an “accident” or illness. While it may seem impossible to take time off, a hospital stay and rehab makes that ‘vacation’ possible. Wouldn’t it be more satisfying to sun on a tropical beach? The challenge is to recognize and acknowledge underlying issues and alleviate the stress before triggering an inevitable accident or illness.

In another happy accident, we paddled into Lexington, Missouri Riverfront Park late one afternoon. After setting up camp, Scott and I waded through the floodwaters to get to town, arriving at the Battle of Lexington State Historic Site after hours. However, the museum was serendipitously open for a board meeting, and we were allowed to tour the exhibits, gaining critical insights into local Civil War history that factored prominently into the newspaper column and book.

Echoes in Time

According to our culture’s linear sense of time, events happen in sequential order, one thing leading to another forward through time. Time, however, is in many ways an illusion, a bi-product of the physical universe. Time moves at different rates according to gravity and speed. Time doesn’t apparently exist outside the universe, implying that everything happens all at once within the Universe, although we may perceive it otherwise. Through personal observation, I’ve often wondered if time flows in both directions, that events in the future echo backwards through the past.

As a teenager I decided that botany was too complicated and decided to write a book called Botany in a Day to make it easier to learn about plants, although I didn’t know exactly what that entailed. I eventually wrote that book, which has become a best-seller, with more than 130,000 copies sold worldwide. It is used as a textbook in many university programs around the globe. In retrospect, I wonder if my teenage vision to write the book was motivated in part by the fact that I did write the book in the future, an event so prominent in my life that the memory echoed back in time to my younger self.

Such experiences may be fairly common. For example, my ex-wife pretended to sort the mail as a child, placing letters between the balusters of the stairway railing. We ultimately bought a small town general store which included a postal contract to sort the mail. Did her childhood fantasy world echo a future memory?

We were far down the Missouri River before I recalled another echo in time, this one directly related to the river endeavor. As a child I wasn’t drawn to the fast and scary rides at amusement parks. But the log ride resonated on a deep level. Sit and take a slow ride up, tick-tick-tick-tick, then crest the top and slide down the watery chute to the big splash at the bottom. Who would have thought that early interest in the log ride would lead to carving my own log canoe?

I didn’t start canoeing until age 31, when we invested in an Old Town canoe as a convenient means to bring our children on wilderness expeditions without resorting to heavy backpacks and a forced march. That first river experience inspired more canoe trips and ultimately led me to found the Jefferson River Canoe Trail to acquire land for paddler campsites as part of the Lewis and Clark Trail National Historic Trail. Immersing into Lewis and Clark history further led to carving the dugout canoe with Churchill Clark and paddling the Missouri River, coming full circle with my childhood fascination with log rides in amusement parks.

Did the forgotten childhood fascination with the log ride lead to one day carving my own dugout canoe, or did the river experience somehow echo back in time to plant the seeds of fascination with the log ride at the amusement park? Some questions are worth asking even if difficult to answer definitively.

Walk the Line

Whatever reality is, I’ve seen enough minor miracles to know that it is not as advertised. There is something more to life than going to school to get good grades to be awarded a job sitting in a cubicle for forty years to retire and die in an easy chair in front of the television. Life is something much more beautiful, mysterious, and confounding.

I’ve often felt that my own path, for better or worse, was pre-determined, and that my role in life wasn’t so much to create my future as to merely intuit what I’d done and do it again. That assurance should be comforting, yet I’ve often found it disconcerting, as if my life doesn’t belong to me. I often feel like an actor trying to remember a play without having seen the script.

The path has never been easy. I’ve worked hard to make my dreams come true, applying thousands of hours to build my own passive solar stone and log house without a mortgage, thousands of hours more staring at a computer screen to write books and establish a publishing company. I’ve worked sixteen-hour days most of my life to make a positive difference in the world, often with less-than-optimal results.

For any glimmer of intuition about the future, it is easy to glom onto that and create logical, rational plans to bring it into fruition. It is only in having those plans blow up in my face that I’ve learned to progressively let go and to trust the path to unfold as the Universe sees fit. The more I learn to trust the Universe, the more I’ve been blessed with minor miracles, like those we experienced on a near-daily basis throughout our five months on the Missouri River. I don’t, however, control the process.

Trusting one’s fate to the Universe is like walking an invisible tight rope across a great chasm with roiling waters below. There is a measure of intuition to predict the path ahead followed by leap of faith that there will be solid rope underfoot. The greatest challenge may be accepting that we own neither our lives nor our death, but must continuously step boldly and blindly into the unknown for whatever that may bring.

For our time on the Missouri River, we committed ourselves and our canoes directly to the roiling waters with faith that the Universe would carry us through. Our final great obstacle was the notorious “Chain of Rocks” after the Missouri merges with the Mississippi, a few miles upstream of our endpoint at Gateway Arch in St. Louis. The subsurface line of concrete slabs, rock, and rebar creates a serious hazard for paddlers, one that we easily floated over thanks to unprecedented floodwaters that fully submerged the Chain of Rocks to the end of the paddling season. We completed our journey of faith and rediscovery on November third, after five months and three days on the river.

Thomas J. Elpel is the author of Roadmap to Reality: Consciousness, Worldviews, and the Blossoming of Human Spirit, as well as Five Months on the Missouri River: Paddling a Dugout Canoe, plus numerous other books on nature, botany, and sustainable living available from www.hopspress.com.

Thomas J. Elpel Personal Website

Thomas J. Elpel Personal Website