As a wilderness survival instructor, I have spent a good deal of my life out practicing skills—sleeping in holes in the ground, eating roots and bushes, starting fires by rubbing sticks together, and trying to figure out how to kill stuff with my bare hands, since it seems like cheating to bring a fishing pole or a gun. These survival skills were the skills of our ancestors, who lived by their hands and wits for most of human history, until the rise of agriculture. But one must wonder if this kind of traditional knowledge is still relevant today.

Speaking at the Bioneers conference in Anchorage, Alaska. October 2011.

It is arguably self-indulgent to go camping in the woods to freeze and starve for entertainment while the whole world seems to be careening towards economic and environmental collapse. Indeed, the practice of survival skills flies in the face of the prevailing conservation ethic, which preaches that we should stay on the trails and leave no trace. As the saying goes, we should “take only pictures and leave only footprints,” not go thrashing through the woods, breaking down trees to build shelters, nor throwing sticks and rocks at the wildlife. But having done these things, I would posit that traditional skills are absolutely relevant today, and that by rekindling our connection to the natural world in this way, we can find answers to some of the most vexing problems that face our species.

Connecting with Nature

The way we relate to nature ebbs and flows with the fashions of our culture, and nowhere is this more evident than in the management of our national parks. Places like Montana’s Glacier National Park, for example, were not set aside out of any particular conservation ethic, but at the request of the Northern Pacific Railroad, to create a tourist destination with ritzy accommodations to entice wealthy clientele to ride the railroad West. Later, the rise of the middle class made the national parks a playground for common people, a place to camp with the family and feed the bears for entertainment. And America’s love affair with the car led not just to drive-in movie theaters, restaurants, and churches, but also to paved roads winding through geyser features in Yellowstone, and drive-through trees in California’s Redwood and Sequoia National Parks.

The prevailing philosophy today is supposedly more ecologically enlightened, and environmental educators often remind us that we are part of the interconnected web of life. Yet, in the next breath, they tell us not to step off the boardwalk. We are told to leave nature as it is, and not touch, pick, or eat anything. It is as if nature has been reduced to an exhibit in a museum. We can look at it, but not participate in it. In many cases it isn’t even legal to gather firewood and build a campfire, not even in the dead of winter, camped miles from the nearest road, in the middle of a million acres of firewood.

This hands-off philosophy isn’t limited to the national parks. It is deeply embedded in our culture, touted by ecologists, environmentalists, wilderness advocates, boy scouts, parents, public land managers, and even taught in public schools. The theology is well intentioned. Our species is clearly devastating the planet. But there is something wrong with an ideology that tells us on the one hand that we are part of nature—and on the other hand that we are the bad part!

As a society, we have embarked on perhaps the greatest social experiment ever conducted. What happens when we tell our children to look at nature, but not to touch it? What happens when kids are herded into organized sports, but never really get beyond the lawn grass to explore, play, or build forts in the woods or gullies at the edge of town? What happens when kids spend all their free time exploring virtual worlds, but not the real one?

Consider the Army veteran who was unable to start a fire in my neighbor’s wood stove, because he couldn’t light a big log with a little match. He had no concept of tinder and kindling, and he was unable to warm up the house on a cold winter day. He is not alone, and I am continually shocked to meet adults who don’t know how to chop wood, or cannot start a campfire without gasoline and matches. We have an entire generation of young people who are very smart, yet don’t know how the world works and don’t know how to take care of themselves. Conceptual knowledge is meaningless without context, much like having a brain in a box on a shelf. What good is it unless you can take it out and do something with it?

Author Richard Louv called the nation’s attention to the dangers of losing our connection with nature in his 2005 book Last Child in the Woods. His book sparked a new back to nature movement, as people began to recognize the importance of connecting with the natural world and having free time to play and experiment in the environment. Even the Forest Service has jumped on the bandwagon with its Kids in the Woods programs in an attempt to reconnect children and nature.

For those of us involved in traditional skills, Louv’s book labeled a problem to which we had already grasped the solution, as implied in the title of my wilderness survival book, Participating in Nature.

In short, what one can learn while playing in the woods is nearly impossible to quantify on a written test, yet essential to our understanding of real-world physics, essential to the quest for sustainability, and essential for sound resource management. In my case, figuring out how to meet my needs for shelter, fire, water, and food in the wilderness provided the proper grounding to address those same needs in society.

Self-Sufficiency

As a child, I lived in what later became known as the Silicon Valley, but every summer we traveled to Montana to visit my grandmother, Josie Jewett. She lived, “up a creek without a paddle,” as she often liked to say, and we kids spent our summers playing in that creek, building forts, and roaming the hills and meadows. Grandma Josie still cooked on a woodstove, and every day she made a pot of herbal tea, using herbs such as peppermint, yarrow, blue violets, or red clover, which we collected on our walks and dried. When we moved back to Montana for my junior high and high school years, Grandma’s house was the one place that I wanted to go every weekend and every summer.

As a teenager and young adult, I indulged in things that our culture doesn’t necessarily view as productive. I had little interest in going to college or getting a job. Instead, I hiked hundreds of miles in the mountains, studying plants, stalking deer, and experimenting with survival skills. Every day was a new opportunity to starve, trying to live on roots that were too small to justify harvesting them, trying to outwit ground squirrels that were smarter than me, or trying to down a dinner of fried grasshoppers and enjoy it.

Every night was a new opportunity to freeze in shelters that seemed like good ideas in the survival books, but didn’t really work in the northern Rockies. The challenge is that you can’t just take a class and get a diploma that says you now know how to survive in the world. You can get the basic idea, but ultimately, you have to go experiment to figure out how these skills apply to your specific environment.

I lay awake, shivering in many cold, damp, or drafty shelters, before I learned how to build some that were adequately warm and dry, or sometimes downright cozy, even without a blanket. Through trial and error, with little more than my bare hands, I learned the fundamentals of sound construction principles and energy efficiency. Lacking a tent or sleeping bag, a thermostat, or a furnace, I became acutely aware of heat loss due to drafts or conduction. Trying to stay dry taught me a lot about proper shingling and ditching around my dwellings. Hauling firewood to my shelters made energy itself tangible and quantifiable and taught me the importance of conservation. Rubbing sticks together and living with fire gave me an intimate familiarity with my energy source in all kinds of conditions, from hot and dry, to cold and windy, drenching wet, or even while sleeping inches away in a grass-lined bed inside a shelter built of kindling.

My greatest fear in life was getting stuck in a job and losing my freedom. I understood that I could not just hang out at my grandmother’s house and tan hides, eat cookies, and go camping my whole life. But I desperately did not want to go the conventional route of going to college, getting a job, and paying down a mortgage until retirement. That seemed a little more complicated than it had to be anyway.

With my background in survival skills, I recognized that it was fundamentally the same issue. We are all on one great survival trip, trying to figure out how to meet our needs for shelter, fire, water, and food—preferably without destroying the planet in the process. That really is the bottom line. How can we sustainably meet our needs for shelter, water, fire, and food without consuming all the earth’s resources, without altering the climate, and without being enslaved to a meaningless job until we die?

The conventional route of getting a job and paying a mortgage doesn’t really work. Conventional houses are way too expensive, and not even very good. Most houses require a furnace and constant inputs of fossil fuels to keep the pipes from freezing and breaking. The bathrooms are virtually guaranteed to rot out halfway through the mortgage. The walls are so flimsy that you can punch a hole through one with a fist. From the floor to the roof, there is an endless parade of ripping out, landfilling, and replacing carpets and cabinetry, furniture, and shingles.

It is any wonder that we struggle with resource depletion and global warming when every person in America is burning up the pavement running back and forth to a job that is generally bad for the environment, just to make a pile of money to throw at their home mortgage, utility bills, and endless repairs? What happens if we hit a recession and don’t bounce back? How long can we maintain the illusion of being an affluent nation?

It made sense to me to focus on the basics and build my own house, figuring that if I had a place to live and no mortgage then I would be free to do whatever I wanted in life. I had no qualifications to build a house, beyond having read some books on the subject, but I was accustomed to making do.

I did know how to start a fire by rubbing sticks together, and with that on my resume I got a job working with troubled teens in the wilderness, and saved up a small nest egg to get started. I married my girlfriend from high school, and together we bought land, moved into a tent and built a passive solar stone and log home for about the cost of a new car. Later, we added solar panels to generate electricity and run the meter backwards, producing on average as much power as we consume. Naturally, the house doesn’t have either a furnace or a thermostat.

Ironically, life’s choices later took us away from home for most of eight years, but I never really worried about the house. We could leave it all winter without risk of freezing the plants or breaking the pipes. The house just sat there sustaining itself. The solar water heater kept producing hot water; the photovoltaic panels kept generating electricity, running the meter backwards. I stopped by every couple weeks and watered the greenhouse, which kept growing greens, and thanks to my brother’s care, the chickens kept laying eggs. And that’s the funny thing about sustainable living. It’s really not all that difficult to achieve and it is far easier than the conventional route. If we had built houses properly in the first place, then we wouldn’t be facing such dire economic and environmental issues today.

I read an article recently outlining ways to create jobs and get the economy back on track. Oddly, one of key suggestions was to provide incentives for foreigners to come to America to start businesses and create jobs, as if we Americans are no longer capable of doing it ourselves. Are we really that far gone as a country, that we are dependent on the charity of others for employment opportunities? Have Americans lost all sense of self-sufficiency, reduced to mere couch potatoes, capable of thinking, but not of doing? What happened to the can-do attitude that built this country?

The reality is that graduating from college with a piece of a paper that says you know something no longer guarantees that you can get a good job. Getting a job no longer guarantees that you can keep it for life, and having a fat retirement fund one day is no guarantee that it will still be worth anything when you actually need it.

Welcome to the new era of self-sufficiency. It is about shelter, fire, water, and food. Whether you live in the city or the country, there are always steps you can take to become more self-sufficient. You can prioritize your expenses to pay down your mortgage faster. You can improve the energy efficiency of your home to become more independent from the power company. You can remodel and retrofit rot-prone materials with something made to stand the test of time. You can collect rainwater from the roof for use as household or irrigation water. You can plant fruit trees to grow free food either for yourself or for children walking down the sidewalk. If you have the skills to take care of yourself, then you have the skills to take care of others, and you will never be short of work. Moreover, if you have your shelter, fire, water, and food in order, then you can choose whether you want to work or not.

Today there are a great many disenfranchised young adults who don’t feel that college is for them, and don’t want to get a job and become hopelessly stuck in the machine for the rest of their lives. I founded a fledgling Green University® to provide a new and desperately needed model for higher education—one where young people can get grounded with hands-on wilderness skills, combined with a healthy dose of do-it-yourself alternative construction and sustainable living skills. It is my hope to eventually mentor participants in green business development, providing a support network to help students incubate enterprises that will make a positive difference in the world.

In addition to mentoring young adults, the highlight of my year is always taking the local junior high kids out for three days and two nights of wilderness survival skills. They sleep in shelters of sticks and bark, even in torrential rains, and sometimes they sleep in piles of grass without even a blanket. They make fires by rubbing sticks together. They make their own dishes; they wade into the swamps and gather cattail roots for food; they cook their own meals, doing such things as a stir-fry using hot rocks on a slab of bark instead of a metal pan, or cooking bread in a stone oven. They stalk wildlife; they stalk each other. They play in the mud; they have marshmallow blowgun wars.

As one student, John, wrote after a camping trip, “I have pondered the simple construction of the mousehut… sticks, grass, and bark piled on each other, but yet it is one of the warmest shelters I have ever encountered. How interesting that a mouse, a hundred times smaller than myself, can survive performing the same tasks we did to make the shelter. Also, how smart this creature must be to come up with this simple, but yet, complex design. In my opinion, you must experience it to fully understand what it is all about.”

I doubt that any one of these kids will ever be in a situation where they have to build a mouse shelter or start a fire by rubbing two sticks together. But I also know that you can ignite something much bigger than a fire with these kinds of skills. Doing hands-on skills connects the brain to the hands and the hands to the world. This kind of hands-on ability not only makes it possible to transform ideas into reality, but also facilitates the flow of information the other direction, from the hands to the brain, opening up a world of infinite possibilities.

Towards a Sustainable Civilization

Perhaps most importantly, the hands-on quest for shelter, fire, water, and food ultimately enables a deeper connection with the natural world. As I wrote in Participating in Nature:

In primitive living you learn about the wilderness as you create your niche in the ecosystem and gather the resources you need for living. For example, to harvest edible plants you have to learn about them. You learn the names and the habitats of plants. You learn about individual edible plants by eating them and by noticing the changes in the appearance and taste throughout the year. As you harvest plants you learn to recognize them throughout the year, as dead stalks, or seeds, or even by the roots. As you seek out edible plants you begin to notice characteristics of the soil; you begin to notice that your desired herb grows better in one type of soil than another.

The knowledge that you acquire is not always scientific, but you develop an acute awareness of nature and natural resources. For instance, you learn the basics of geology as you look for different types of rock that are useful as tools in primitive living. You might look for quartz, quartzite, or chert rocks to use as “flint” in flint and steel fire starting. Or you might look for sandstone to use for sanding arrow shafts or bows, or to abrade a stone tool. You might look for a clay deposit for making pottery, or for various minerals for mineral paints. You learn about geology as you spend hours searching the riverbank for the right piece of round, symmetrical, fine-grained rock for a hammerstone. You begin to notice if the rocks around you are igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary. Instead of merely hiking from point A to point B, the process of hunting and gathering makes you investigate the land around you.

This intimate connection with nature isn’t just critical to our own well-being, it is essential to the effort to conserve nature. The bottom line is that the more you know about something, the more you care about it. The more you care about it, the more you will work to protect it. One of the greatest threats to wilderness and wild places is a lack of cars at the trailheads. If we reduce nature to mere wallpaper — something to look at, but not to touch — then who is really going to care about it or advocate for it?

As another student, Chas, wrote after the three-day camp-out, “It has always seemed to me that nature is like a piece of artwork, fragile, but only to be admired through the gentlest of hands. We go walking on a weather-beaten path that so many have followed, but never step off to travel farther into the heart of the forest. I now know what it is like to go into the depths of the forest, experiencing the full force of the wild. Nature is not a picture. It is much more than that.”

Some of the most successful conservation groups, such as Ducks Unlimited or Trout Unlimited, are driven by consumers of nature — people who work to expand habitat and breed more ducks and more trout because they like to hunt and fish for them. This act of participating in nature effectively increases the demand for more nature. As ecologists and environmentalists, we need to adopt this new paradigm and help the populace reconnect with the natural world before we bulldoze and develop everything that is left.

As Spencer wrote after the camping trip, “The outdoor classroom experience has given me a more in-depth look at nature and our ancestors than any movie or text book has or ever will. Living in the outdoors has shown me that nature is full of surprises and that it provides everything that we need to survive. If more schools took their students on outdoor trips like we do, humans might learn to be more conservative and save our world.”

An experiential connection with nature is in fact imperative if we are to conserve and sustainably manage our natural resources. Consider energy. What happens when people grow up without a quantifiable sense of energy or knowledge of where it comes from when they flip on a light switch? How can we formulate sensible energy policy or steward our resources when energy itself is an abstraction?

If you spend enough time living with fire, you can develop a quantifiable sense of energy. You will know approximately how much heat and light a given pile of firewood produces, and from that you can better extrapolate to make meaning out of energy policy concerning coal, oil, gas, or the various avenues of generating electricity. Likewise, if you have a solar water heater, you can temporarily turn off your electric water heater, to experientially discover just how much hot water a solar water heater produces according to the weather and the seasons.

My local utility would very much like to construct a massive transmission line, with fourteen-story tall towers, down our local section of the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail. It is being touted as a “green” energy project because it would serve partly as a conduit to send wind energy from Montana south to markets in Las Vegas and California. But it doesn’t take rocket science to figure out that there is nothing remotely green or sustainable about building this kind of industrial infrastructure and ramrodding it through virgin land. It would be far more sensible if utilities installed solar water heaters for their customers and took care of any maintenance, just as some utilities still come around to light customers’ gas furnaces each fall. Rather than each customer researching solar water heater brands and installers, the utility could take advantage of volume-pricing to install thousands of identical units, charging customers for some, but not all of the energy they save. In effect, the customer would get a small discount on the monthly utility bill, while the utility would get to sell the same electricity twice. That would constitute green energy policy.

A Deeper Connection

There is one more thing you may begin to see when you spend enough time in nature and begin to connect on a deeper level. You can begin to see the things that are no longer there.

That is perhaps the greatest irony of our cultural disconnect with nature. If you don’t know what lives outside your window, then you will not notice if it disappears, either. In fact, you can take a lush and forested ecosystem and completely denude it, and if it happens slowly enough, than nobody will notice any difference.

I’ve walked thousands of miles across several western states, looking at the ground. Prior to the domestication of livestock, semi-arid rangelands took care of themselves. In North America, massive herds of buffalo migrated across the West, sticking together for protection from predators. These herds nuked everything in their path. Anything not eaten was trampled into the soil, effectively planting fresh seeds while providing a mulch cover of organic matter and manure.

Today our rangelands suffer most from a lack of animal impact, so new seeds don’t get planted. The bare ground between the plants keeps spreading, even when the existing grass grows tall and green. In places like west Texas or South Africa, where the wild animals were too numerous to count only two hundred years ago, the land supports only a handful of cows over hundreds of miles today. The same process is happening all the way north to Montana, but almost nobody has a clue, because most people are too removed from nature to know what they are looking at on the ground, and whatever you see out the window looks completely normal, as long as you have nothing else to compare it to.

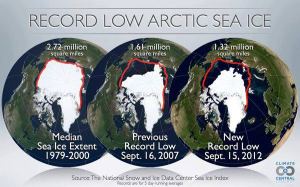

Moreover, the thing that makes the soil brown or black in the first place is carbon that has been extracted from the atmosphere and, in the case of rangelands, trampled into the ground to build soil. Grasses grow rapidly, and grasslands can sequester significantly more carbon per acre than forests. We’ve not only shut down the sequestration cycle on every continent, we’ve also oxidized half or more of the organic carbon from most crop and rangelands back into the atmosphere. And we wonder why we have a global warming problem.

It is hard to imagine now, but people once hunted pigs in the forests of Israel. Greece was also covered by rich Mediterranean forests. The fertile fields of Libya once grew grain for the Roman Empire. Is it any wonder that people fight all the time in places like Libya, Afghanistan, or Iraq, where the land has lost its fertility?

We may see on the news that the capital of China is in danger of being buried under sand dunes, but what we don’t see is that we are also turning the American West into a new Saharan desert. You can watch it happen year by year if you are accustomed to looking at the ground.

The problem can be easily remedied once it is understood, and with proper soil management, we could potentially put the brakes on global warming. Yet, the ground beneath our feet is functionally invisible to most people. Perhaps we could see it better if we took off our shoes and got back in touch with the earth.

I like to think of primitive living as a metaphor for living in the modern world. The metaphor reminds us that we are part of the ecosystem and we have no choice but to take from it. But in the quest to meet our needs for shelter, fire, water, and food, we learn about ourselves, we learn about the ecosystem, and we become empowered to make a difference in the world. Playing in the woods won’t solve all the world’s problems, or necessarily any of them. But it can point us in the right direction, and direction is perhaps what we need more than anything else.

Thomas J. Elpel delivered this as the keynote speech at the Bioneers conference in Anchorage, Alaska in October 2011.

Thomas J. Elpel Personal Website

Thomas J. Elpel Personal Website