Freedom to roam has been a fundamental right for Montanans from before statehood, lasting until recent times. I was privileged to grow up with that culture of open access, when fences were intended for livestock, not for people. Unfortunately, people unfamiliar with Montana traditions bought land and posted the first No Trespassing signs. Acre-by-acre, property-by-property, the people of Montana lost access, and with it an essential part of our identity.

Montanans cherish a deep connection to nature, they always have. Yet, without the right to roam across the open countryside, children grow up on paved or gravel roads, manicured lawns, and mind-numbing electronics. That isn’t the Montana way. Ask any middle-aged or older person about growing up here, and most will reminisce about rambling the countryside, hiking, fishing, and generally exploring, passing through fences regardless of property boundaries.

Freedom to roam goes hand-in-hand with nurturing a sense of respect for the land and landowners. Those who remember owning the freedom to roam were unlikely to leave gates open, cut fences, litter, or vandalize properties. Those are symptoms of bored and disconnected citizens, lacking an ethic of stewardship. Montanans can restore the right to roam, better described as the “right of responsible access,” and with it, we can cultivate a renewed sense of stewardship and respect for the land and landowners.

Subjugation

Freedom to roam was widely considered a basic right in early America, enough that the Pennsylvania delegation proposed a right-to-roam amendment for the U.S. Constitution, wrote Ken Ilgunas in This Land is Our Land. Unfortunately, the amendment was not adopted and was likely regarded as unnecessary. Walking across private property was as natural as walking down the road. People knew they could walk across each other’s lands and forests while being respectful of crops, livestock, tools, structures, and privacy.

Freedom to roam was so deeply embedded in early American culture that people didn’t think to ask permission. Why ask for something that already belongs equally to all? Asking would have implied that wanderers needed permission to cross private land. A few cases that were contested in the courts typically involved egregious abuse of private land, such as militia training or cutting down a large number of trees. Yet, so strong was the custom and precedence of public access to private land in early America that the courts ruled in favor of wanderers, not the landowners.

The cultural shift towards private property rights began in the wake of the Civil War. Having lost the war, southern states passed private property laws to prevent newly freed slaves from hunting, foraging, or even walking across white-owned land, subjugating them to a lower social and economic strata.

Property rights culture spread from the South, slowly shutting down freedom to roam for people of all races. It happened one private property sign at a time. It was annoying when outsiders posted the first No Trespassing signs here in Montana, but people adjusted their routines to walk elsewhere. We lost the state a piece at a time until we effectively lost all private land access. Worse than losing the right to roam, Montanans became conditioned to fences as corrals for people, subjugating ourselves like livestock.

Moreover, posting property to keep people out fosters idleness and thus boredom, which can lead to vandalism and abuse that makes No Trespassing signs seem necessary. If we wish to raise a populace that is fit, healthy, responsible, and free, then we must reflect on the meaning of freedom and whether private property rights conflict with our ideals as Americans. We can start by comparing our expectations of freedom with those of other countries.

The Everyman’s Right

Touring in New Zealand for five weeks, I did not encounter a single No Trespassing or Keep Out sign. The most stringent sign I saw was a “Multiple Hazard” warning, cautioning people about entering farmlands with active farming operations. On the other hand, the country also has an amazing system of trails or “tracks,” as they call them. These tracks are easily accessible trails, providing little incentive for anyone to trespass.

I learned from talking with locals that New Zealand laws and customs are very access-friendly. For example, most beaches and watercourses are considered public property. I enjoyed walking one public track along the waterfront near the town of Paihia, along the Bay of Islands. The track meandered along private properties where at times the trail skirted along a tool shed, or a brushy hedge served as an impediment to straying into a yard, or in rare instances a fence blocked view into a house, but always the track always took precedence. As long as people have the ability to walk unimpeded, what need is there to trespass?

Access to watercourses includes every perennial or intermittent stream across any pasture or down any hill, with public access along either side to the width of the “Queen’s chain,” or about sixty-six feet. In addition, New Zealand has an extensive network of “paper roads” across otherwise private property. These public right-of-ways were defined when the land was settled and surveyed, and they remain legally open to public use, even if roads were never built.

In addition to access-friendly laws, it is culturally acceptable for New Zealanders to cross private property, although it is considered polite to ask when crossing private property near a farmhouse. Conversely, it is culturally unacceptable to lock people out. One local mentioned neighbors who migrated to New Zealand from Pennsylvania and bought a large farm. The newcomers could not legally close the public track across their land, but in order to discourage anyone from using it, they let the trail grow so thick with brush and tall grass that nobody wanted to go there. Neighbors frowned at the inhospitality of these American transplants!

While touring New Zealand, I appreciated the fact that litter was relatively scarce compared to the states. Of the litter that was there, I wondered how much of it was dropped by American tourists who have lost their sense of connection and stewardship of the land. I realized that No Trespassing signs are also a form of litter, an eyesore on the landscape. It was refreshing to travel in a place that wasn’t marred by inhospitable signs tacked to fence posts.

The idea that people should have freedom to roam is not unique to New Zealand. It is also a long-standing tradition in Scandinavian countries. In Sweden it is known as allemansrätten or “the everyman’s right.” Centuries-old traditions have been coded into law in recent decades across Europe.

In Norway, Sweden, and Finland, people have the right to hike, ski, camp, and forage for wild food on undeveloped private properties, provided they respect landowners and don’t harm the environment. Bicycling is also allowed where appropriate. While the public is not allowed to enter cultivated lands during the growing season or pastures when livestock are present, other times of the year are okay. Similar customs and laws are found in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Austria, Switzerland, Belarus, and the Czech Republic.

England and Wales recognized everyman’s right to roam in the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, while Scotland recognized the right with the Land Reform Act of 2003. Scotland recognizes the public right to walk, bicycle, ride horseback, and camp on private lands, provided that visitors don’t damage the environment or interfere with farming or other private land uses.

Europeans visiting the U.S. are often dismayed to discover they are not allowed to walk anywhere in the “land of the free.”

A Montana Tradition

In my home state of Montana, freedom to roam has been a custom, tradition, and presumed right since the days of the frontier. Trappers, traders, gold seekers, homesteaders, and cattlemen traversed the country in every direction by foot and horseback. The tradition of open access continued long after livestock fences went up. That was the world I knew as a youth, hopping across fences as if they weren’t even there.

As a teenager in the 1980s, I lived in Bozeman and walked nearby farm fields regularly where I tracked foxes, pheasants, and skunks in snow-covered fields. In a tangle of brush along an irrigation ditch, I built a hut of sticks and grass thatching, deepening my connection with nature. During weekends and summers, I went to my grandmother’s house in the country, where I walked for miles in every direction, crossing livestock fences all the way.

No Trespassing signs are a recent phenomenon, first introduced by wealthy newcomers who, oblivious to Montana’s tradition of openness, imported their own cultural expectations. Orange paint on a fence post signifies the same thing as a No Trespassing sign, so we gained a few signs and a lot of orange paint while losing access to millions of acres of land. Sadly, there wasn’t a public debate about it, because our cultural values were neither recorded nor publicized, and the loss occurred slowly, property by property across the state.

People were unaware that by posting No Trespassing signs, they were not only closing access to their own land, but also encouraging neighbors to do the same. Unfortunately, “the everyman’s right” to roam was never formalized into law, nor was it written down as a guidebook for new residents. Is it really too late to recapture our lost freedom?

Landowners express liability concerns as an excuse for posting their property, worried they might get sued if someone were injured or killed scrambling over rock outcroppings or impaled on a century-old piece of metal sticking out of the ground. However, according to Montana’s Recreational Use statute (§70-16-302, MCA), “A person who uses property […] for recreational purposes, with or without permission, does so without any assurance from the landowner that the property is safe for any purpose.” Landowners are potentially liable only if the visitor has paid a fee to be there, or in cases of “willful or wanton misconduct” by the landowner. Any natural or artificial hazard on the property, such as a natural or man-made fishing pond, is considered a “condition of the property,” for which the visiting recreationist accepts all responsibility.

The cultural shift can be shocking to someone who experiences it for the first time. I met one Montana rancher who spoke of how much he enjoyed seeing people fishing streams on his property. Then he retired and sold his ranch. He was dismayed to see that the new owners posted the property, and then even he was not allowed to revisit the land despite having lived there for decades.

Journey of Discovery

In 1804 through 1806, Lewis and Clark led the Corps of Discovery on an expedition up the Missouri River, over the Rocky Mountains, and down the Columbia, in search of a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean. They didn’t find the Northwest Passage they had hoped for, but their journey of discovery led the nation westward and continues to inspire people today.

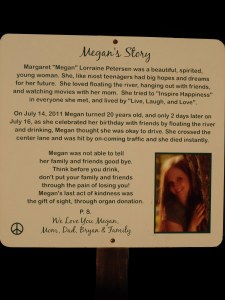

Similarly, individual journeys of discovery can be deeply powerful experiences that shape a person’s life. For example, after the devastating loss of her mother and her marriage, Cheryl Strayed rebooted her life alone on the trail, as told in her best-selling book Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail, later retold as a Hollywood movie.

Having the freedom to engage in a journey such as this is a basic need and fundamental human right, “the everyman’s right,” that should be easily accessible to all people, especially young adults who are searching for their path in life. Every person should have the opportunity to walk or paddle and camp to the horizon and beyond in their own journey of discovery.

I have undertaken several such journeys myself. In 1988, at the age of twenty, my high school sweetheart and I walked five hundred miles across Montana, starting at my grandmother’s house in Pony and ending at Fort Union on the North Dakota border.

We first walked across private farm fields from Pony to Three Forks, then followed the active railroad down the Missouri to Sixteen Mile Creek. Our map still showed the tracks of the former Chicago Milwaukee Railroad ascending Sixteen Mile, but here the tracks had been removed and there was a locked gate plastered with No Trespassing signs.

I understood the words well enough, but the idea was incomprehensible to the free-roaming lifestyle I’d grown up with. Not having anywhere else to go, we climbed over the gate and followed the rail bed upstream over wooden trestles and through convenient tunnels. We saw 28 elk and 250 deer that day.

The property manager found us camped by the creek, but fortunately decided we were harmless enough and let us continue our journey. The next big ranch was also posted, but they invited us to join them for hamburgers. Most people we met were supportive of our adventure. A few were mildly disgruntled and suggested that we should be responsible and get a job, but waved us onward. Journeys such as this have been greatly empowering, giving me the confidence and determination to follow my dreams in life.

The consequences of posting property runs much deeper than may be readily apparent. Fencing people out is effectively the same as fencing them in. A person who cannot walk out the door and across an open field is living in a cage.

Zoo animals are known to have severe psychological disorders from living in cages. Cages impact people too. I’ve met many young people who are angry at society, angry at the machine of civilization, angry at the way the system enslaves and dehumanizes people. Having grown up constrained by fences, they feel trapped by society, as if they lack freedom to live their own dreams. Conditioned to being in a box, they do not recognize freedom even when they have it. I’ve had summer guests who would not think to walk off my homestead on their own, even though there is 100,000 acres of public land accessible via a short walk up the road.

Like my horse who would pace back and forth along an invisible fence after I removed the electric wire and plastic posts, these young, well-intentioned people were controlled by fences even when there were none.

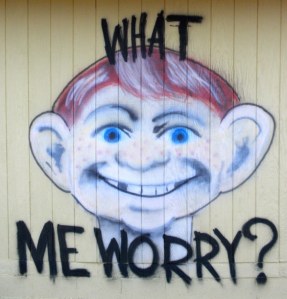

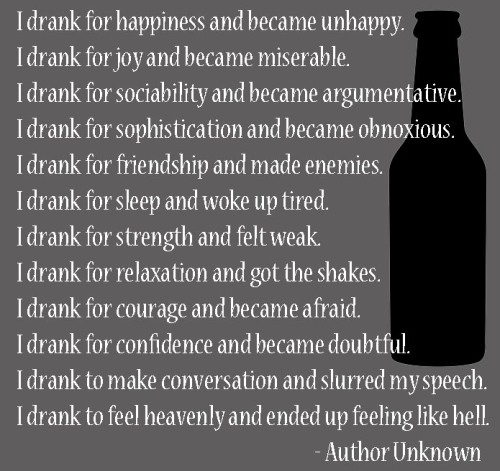

Other people may not feel the same depth of malcontent or may not verbalize it the same, but a sense of confinement underpins some of the biggest issues we face as a society, from alcoholism to drug abuse, obesity, and a simmering cauldron of civil unrest that threatens to undermine our country.

Having grown up without cages, I felt free to pursue my dreams in life even if I didn’t have the traditional credentials or certification to do so. I built my own passive solar stone and log house without a mortgage, did my own plumbing and wiring, stared at blank pages long enough to launch a successful writing career, and I’ve successfully incubated three businesses and a nonprofit organization.

I worry about the future for our young people who have only known cages. Freedom to roam is critical to inspire a new generation of thinkers, doers, and leaders. How will people think outside the box to solve humanity’s most pressing problems if they’ve grown up inside walls of No Trespassing signs?

Limitations of Public Access

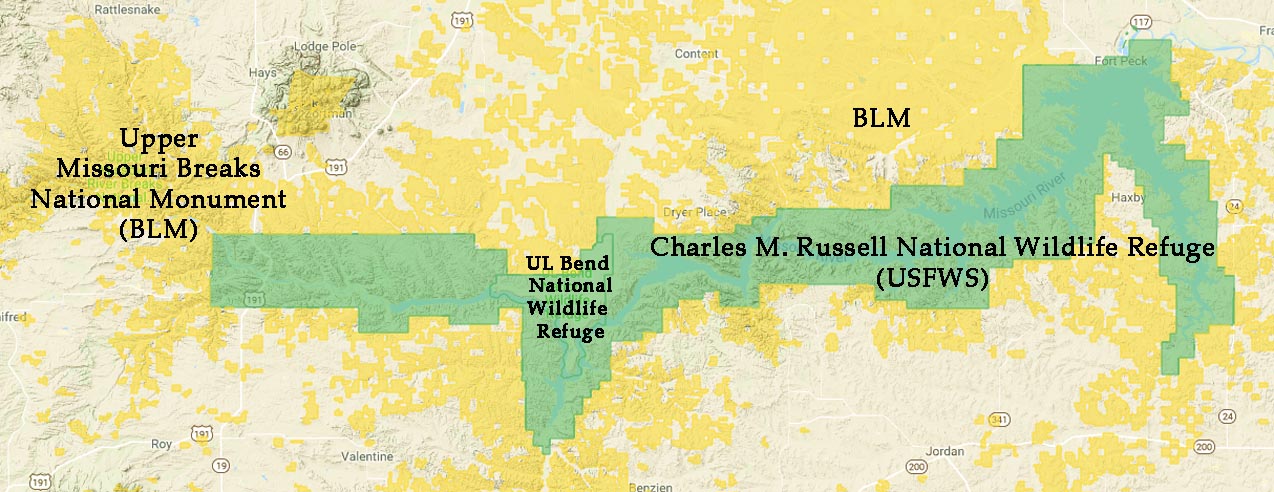

The logical citizen response to the rise of No Trespassing signs is to seek better access to public lands, which is an essential, yet inadequate step to meet the level of need. Here in Montana, we are blessed with large tracts of public lands, comprising nearly 30 percent of the state. Public officials continue working to secure legal public access to tracts that didn’t previously connect to public right-of-ways. A never ending series of court battles also work to maintain established public routes through private lands.

Even with generous public access opportunities, people are forced to drive past miles of open farmland and forests to reach legal access points, causing car dependency, more traffic, more pollution, bigger parking lots at trailheads, and increasingly congested, eroded trails.

Ironically, some private landowners have blocked access to public lands to their own detriment. For example, Beall Creek in the Tobacco Root Mountains has no formal public access, and consequently, the forest trail has fallen into such disrepair with logs across the path and bridges rotted away that it is difficult to walk anywhere, so now the watershed is largely unusable even to the people who live there.

Montana does, however, retain a friendly trespass law, which states that a person is allowed to enter private property as long as it isn’t posted or painted orange at any obvious entry points and the landowner hasn’t verbally or otherwise stated that the visitor is unwelcome. Any rural property that is not posted is theoretically open to public access.

Montana has some of the best stream access laws of any state, which have been codified in law and protected by the courts, thanks to the tireless efforts of advocacy groups, such as the Public Land/Water Access Association, Inc. PLWA has thwarted numerous attempts by out-of-state landowners and their attorneys to claim the land for themselves and lock the public out.

In some states the rivers are considered public, but the land underneath is not, such that a person is technically trespassing if they step out of a boat. But in Montana, anglers can float down a river and get out to fish or camp anywhere “within the ordinary high water mark,” provided that their camp is not too close to a neighboring home.

As an avid hiker, I typically spend my summers exploring public lands in the mountains, but when winter comes and the mountains are deep with snow, I forgo the winter boots and keep my regular shoes to hike across thousands of acres of low-elevation private lands, principally along the Jefferson River. I’ve come to know a lot of special places along the river, and I’ve been alarmed to see development and No Trespassing signs chip away at the integrity of the Jefferson.

Thus, I founded the Jefferson River Canoe Trail (www.JeffersonRiver.org) and led group efforts to secure quality public campsites while encouraging conservation easements along the river corridor. The water trail includes several previously ignored scraps of public land, which we named and claimed as campsites. Each campsite has different recreational opportunities, in some cases connecting public lands where canoeists can hike and explore while journeying down the river.

With overland travel largely banned, water trails become the best available substitute because they cut through private lands, enabling ordinary people to experience their own journey of discovery.

Rail trails cut through private lands much like water trails, yet unfortunately, Montana is far behind other states in securing old railroad beds for public trails, permanently losing vital trail opportunities. I have enjoyed bicycling rail trails in Idaho and South Dakota with my kids, but have not found any rail trails in Montana long enough to allow for multi-day touring.

Most other states have been more proactive with legislation claiming abandoned railroads as public rail trails, but Montana did nothing, letting easements on most old railroad beds fall to private landowners, losing hundreds of miles of potential rail trails across the state. Advocacy groups are working to reclaim abandoned rails across public lands for trails, but railroad beds on private lands rarely become public again.

As part of the effort to replace lost access, our state passed legislation allowing public use of state lands that are leased out to farmers and ranchers, provided there is legal access to those properties. The state’s Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks has also set up a Block Management program where landowners are compensated to keep land open to hunters.

Thanks to the Stream Access Law, water trails, Block Management, and efforts to purchase public access routes across private lands to public lands, Montanans are trying to recapture our freedom to roam. Yet we can do much more to improve access here and to provide a positive role model for other states to follow.

Chicken and the Egg

In school we were taught that laws are passed by the legislature and enforced by the courts. Reality works somewhat differently, such was the case with Montana’s Stream Access Law. When outsiders bought riverfront property then attempted to claim rivers and streams as their private property, advocacy groups sued on the grounds of longstanding precedence of public use. The courts agreed and directed the legislature to create the Stream Access Law to codify traditional practice. Montana’s Stream Access Law was built to reflect court rulings. The court ruling therefore became the law.

Montanans similarly owned the right to roam the open landscape since before statehood. Unfortunately, when the first No Trespassing signs were posted, citizens failed to take the landowners to court, and we lost the freedom to roam through forfeiture. Walkers grudgingly shifted to non-posted parcels until those too were closed to the world.

Today, the issue of corner crossing remains unresolved. A corner crossing is the point where two public parcels meet at their corners. Geometry dictates that the meeting point is infinitesimally small. A person must physically enter adjacent private property to move from one public parcel to another, which could be argued as trespassing, even if the hiker or hunter never sets foot on the ground while scrambling over a corner fence post.

The issue has not yet been tested in the courts, and thus far efforts to codify corner crossing into law have failed in the state legislature. This seemingly small issue is actually a big deal, given that much Montana is a checkerboard of public and private lands. The legislature could settle the issue with a public access law, or it may be settled first by the courts if a landowner attempts to charge a walker with trespassing for corner crossing.

Not knowing which way the courts would rule, it is important to advocate for a law in favor of corner crossing. We also need to initiate a broad dialogue about restoring the right of responsible access.

Allowing people expanded freedom to roam can foster a greater sense of stewardship and gratitude, which ultimately reduces vandalism and litter. It is much like the question of the chicken and the egg… which comes first? Do we restore freedom to roam and hope for reduced vandalism and litter, or do we first nurture a greater sense of stewardship to prepare Montanans to reclaim the right of responsible access?

Reclaiming our Heritage

The nonprofit Western Sustainability Exchange published a Welcome to the West guide to educate newcomers to Montana about key issues that many people don’t otherwise consider. For example, people often see a beautiful site and decide to build a house in the middle of it, not realizing that they are damaging exactly the asset they valued. All newcomers to the state should be provided with this Welcome to the West guide, and a section should be added to educate newcomers about the Montana tradition of open space and open access. We also need a statewide educational campaign to encourage landowners to paint their fence posts green to welcome responsible trespassing.

In addition, we need to reconnect our young people to the land and its natural beauty to ensure that they will honor and respect both private and public property. One way to achieve that is to encourage partnerships between public schools and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, such that every school adopts, monitors, and helps manage and maintain state parks and local fishing access sites. FWP can benefit from student labor to help repair old picnic tables, fire rings, outhouses, or other facilities, as well as help with weed control, picking up litter, and collecting data on vegetation and wildlife populations. Students can benefit from the experiential real-world opportunities while developing a sense of ownership and stewardship that will carry forward whenever they visit other sites around the state.

We can also expand the Montana Conservation Corps (MCC) and encourage young people to do a year of service between high school and college, working with the MCC to build and maintain trails, again cultivating an ethic of stewardship and a love for the outdoors that will stay with them for life.

Seniors need not be left out. We can encourage retirees to adopt a local fishing access site or nature trail to help keep it clean and maintained for the next generation. State and federal agencies are understaffed and overworked. Anyone can volunteer and ask what needs to be done. Being a good steward is the first step to honoring our true freedoms.

In Montana and across our nation, outdoor recreational opportunities are essential to the wellbeing and quality of life of the people. In lieu of a codified “everyman’s right,” we need to expand water trails and rail trails and facilitate access to existing public lands. Just as importantly, we need to initiate a dialogue about the longstanding tradition of public access to private lands and bring awareness and desire to reclaim our essential heritage to freely roam the open countryside.

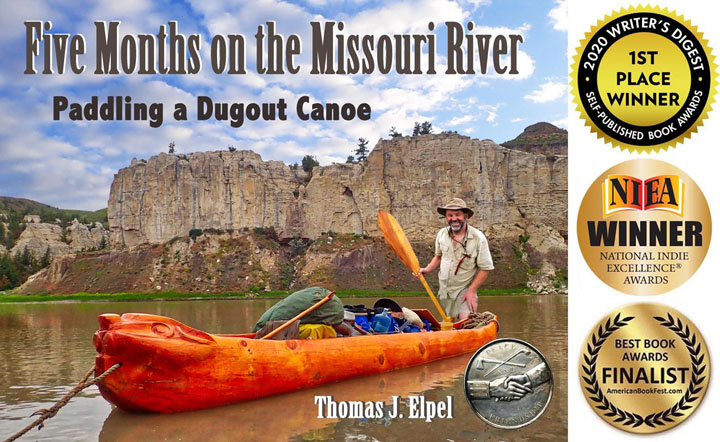

Thomas J. Elpel is the award-winning author of Five Months on the Missouri River: Paddling a Dugout Canoe and numerous other books on nature, wilderness survival and sustainable living. He is the founder and director of Outdoor Wilderness Living School, LLC (OWLS), dedicated to reconnecting children and nature. For adults, he founded Green University® LLC to “connect the dots from wilderness survival to sustainable living skills.” Elpel also founded HOPS Press, LLC and the Jefferson River Canoe Trail.

Thomas J. Elpel Personal Website

Thomas J. Elpel Personal Website